Date of document publication: 2024-01-30

Introduction

This documentation outlines prototyping conducted from January to June 2023. Over this six-month period, the project team developed a system which allowed the researchers Imogen Coulson, Ermeline de la Croix, and Eiloghosa Obobaifo to develop vocabulary lists for archival material. These lists were then used to ‘tag’ archival and photographic materials where the vocabulary appeared. The vocabulary can now help users explore the digitised archival and photographic material accessible on the platform, filtering by name, geographical location, date and object in the Digital Benin catalogue.

Developing Linking Terms

Digital Benin received data from archives, libraries and museums about documents stored in these institutions. Today, institutions store digital assets in different database structures with variable vocabularies and filing systems. It is a priority of Digital Benin to preserve the way institutions store and describe their digital assets because it provides our users information about the institutional (data) history, archival organisation and hierarchies, gaps and more. This local data embeddedness is also described in the source guides, giving an institutional context to the files shown in the archival explorer. Without a data standard used by every institution – and with our priority to value each institution’s own method of archive organisation – Digital Benin requested the original data structure, connecting the data through standardised terms that allow a search across all datasets. Thus, we could include data from institutions that do not have technical staff, and we created a low tech barrier for any transfer method (e.g., access to file repositories, email attachments) and file format (e.g., .pdf, .jpg, .tiff, .docx).

The way files were organised in relation to the archival material also differed among institutions. For example, sometimes one file was a single item (e.g., a multiple-page PDF); in other cases, each page of an item was sent as an individual file (e.g., a JPEGs or TIFF for each page of a diary or piece of correspondence); and some institutions shared large multiple-page PDFs (i.e., with more than 500 pages) that contained numerous correspondences, invoices, receipts and so forth. The team was faced with the challenge of how to collate this material and make it accessible and searchable on the platform.

The project team therefore identified that a common aspect across the variety of material was that these files, which we called ‘archival objects’, could either be divided up or grouped together as ‘archival documents’.

Archival Documents

We defined an archival document as a document produced during a specific temporal event and by or for a specific person – for example, a piece of correspondence written from one person to another on a specific date, an invoice from one person or company to another or a report written by one person or more and published on a specific date.

Each archival document was tagged with the following terms:

Document Type

These are terms taken from the vocabulary of the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus, e.g., correspondence, invoice, price list and research notes.

Names

This list originated with the provenance names from the object data. The research team began to add new names as they were identified in the digitised material. Names were tagged either as the ‘source’ of the document, a ‘mention’ in the document or the ‘target’, i.e., the recipient of a document.

Production Date

Dates were added (in ISO format) for the beginning and end dates of the production of an archival object.

Location

These locations of production were recorded when identified in digitised material and standardised to reflect contemporary place names.

Object Group (Edo Designation)

The Edo designations were taken from those that can be found in the Ẹyo Otọ digital space. These were tagged where objects that fit these terms could be identified.

Specific Object URL

When it was possible to identify a specific object included in the catalogue, researchers included the Digital Benin URL for the object. To ensure the correct objects were identified, this was typically done only when an accession, collector or other number/ID could be identified in the document, accompanying metadata or filename. On the small number of occasions where an image of an object was included and the object was unusual, researchers may have been able to identify the specific object and add the URL. For more information on how researchers were able to identify objects by IDs and numbers, see here.

The research team – Imogen Coulson, Ermeline de la Croix and Eiloghosa Obobaifo – used these terms to connect data across datasets transferred by the institution. This research incorporated a number of skills that the researchers brought to the process, including reading handwriting from historical sources, knowledge of multiple languages (e.g., English, French, German, Edo) and knowledge of the historical context for the materials related to the historical Benin objects.

Having identified these terms, Digital Benin researchers noted that further contextual information and descriptions were needed to situate these documents or archival objects within the larger group of items they were part of in the holdings of each institution. Researchers then began the process of grouping these archival objects under ‘archival units’.

Archival Units

For each institution, Digital Benin researchers have organised the material received and described it at the level of archival units. These archival units describe the larger groups that the archival documents and objects shared with Digital Benin sit within. Each institution that provided Digital Benin with data has its own unique history and way of describing and ordering material, often within a hierarchical schema. Each archival object varies in size, scope and level of cataloguing. For example, the Pitt Rivers Museum shared seventeen PDF files which were part of the Pitt Rivers Mss Nevins collection. By bringing each of these PDF files under the archival unit ‘Pitt Rivers Mss Nevins’, these items could be grouped together in a manner which reflected how they were catalogued at the holding institution, rather than listed as individual files.

Additionally, the project team was acutely aware that when carrying out research in archives or photographic collections, it is useful to understand the context of the material, how it came to be in the institution’s holdings, whom it came from and which other material it relates to, either within that institution or in others. Where possible, this sort of contextual information is brought together as a source guide for users of Digital Benin. The team recognised the potential of a source guide to not only collate archival and photographic materials held in disparate institutions but also to bring together knowledge and context about these items.

At the level of the archival unit, Digital Benin researchers included descriptions which provide additional information on the context of the material. Other information to help improve access was also included at this level – for example, copies of finding aids or hand notes, if these were shared with Digital Benin; URL links to the relevant pages of an institution collection’s online database; and a selection of ‘useful references’, typically publications that relate to the archival unit in question.

Reference Code

This is the code given to a group of material by the institution itself. Not all institutions gave material a reference code; therefore, this space may be blank.

Department/Collection

If material comes from different departments or collections within an institution, this is listed here. For example, this space may show which material is held in the archive and which material is held in the photo archive. This is not relevant to all institutions or the information was not provided by all institutions; therefore, this space may be blank.

Title

This is the short title attributed to a piece of material by the institution. The original language of the title has been kept by Digital Benin.

Brief Description

This description was authored by the Digital Benin project team and based on research they carried out between January and July 2023. Information and assistance provided by staff at many of the institutions was extremely valuable in writing these descriptions.

Finding Aid

In cases where finding aids, sometimes referred to as hand notes or collection catalogues, were shared with Digital Benin, these were included. These aids can be extremely detailed and provide further information on the contents of archival units (as defined by Digital Benin).

URL

When possible, URLs linking to the material on the institution’s own website were included. These links typically lead to the relevant page of an institution’s public-facing database or where the material has been made available online in digital form. A URL is not available for all items.

Useful References

Useful books, articles, and other resources have been collated here when possible. These may be articles or books written on the material in question or on the person who made/collated the material, or publications written by the individual who provided the material.

Identifying and Tagging People, Institutions, Organisations and Societies

The foundation of the names list was the list of provenance names compiled between 2020 and 2022 using object data. This list can be viewed in the Provenance space on the Digital Benin platform. More information on how this list and research was carried out during the first phase of the project can be viewed in the Provenance Documentation. As more archival and photographic data was acquired from institutions, Digital Benin researchers added new names to this list. Names of people, institutions, organisations and societies were added so that researchers could trace the different kinds of names present in archival material (either as the source of the material, as being mentioned in it or as the target/addressee). As with the provenance names, the new names were standardised in their spelling and other variations, such as ‘Last Name, First Name’ or ‘Last name, F. N.’, in order to link all the archival documents related to each name. The institutions were added and tagged under their official name last used for the institution (e.g., ‘Museum am Rothenbaum. Kulturen und Künste der Welt (MARKK), Hamburg’ was used even when mentioned under one of its former names, such as ‘Museum für Völkerkunde, Hamburg’).

In addition, researchers added the title(s) (e.g., Mr, Mrs, Dr, Prof.) and role of these people, institutions or organisations (e.g., member of the colonial military campaign on Benin, curator, art government agency, company) where it was relevant and identifiable from the data. These roles make it possible to search and compare archival material even for names that are unknown to our users. For example, a query such as ‘show me all “Correspondence” written by “Dealers”’ is possible through the identification of document types and roles. The URLs to the Wikidata or British Museum biographical entries were added where possible. Extensive research into the biographies of all individuals is still outstanding.

Imogen Coulson and Ermeline de la Croix identified over two hundred Edo names in archival material, particularly in the papers of Robert Elwyn Bradbury, where informants were recorded by name by Bradbury, an Edo speaker, and his assistants (Fforde 1973: x). However, as Edo is a spoken language and the spellings used in these documents reflected the way Bradbury and his assistants transliterated the spoken language, the spellings were variable and differed to contemporary orthography and written Edo standards. In other archival and photographic material spellings also vary, as these names were written by non-Edo speakers. Researchers often found that Edo people’s names were recorded in the archival material with their title as their name, or sometimes a combination of title and name. It was therefore necessary to adapt the standardisation described above. Through conversations between Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie, Eiloghoso Obobaifo and Imogen Coulson, it became clear that this was partly because of the fact that in Benin Kingdom, when a title is bestowed upon an individual, the title becomes their name and might indicate how that person would want to be identified. Therefore, Edo titles were left in the names of these individuals (e.g., Esogban N’Iyamu). In cases where the name was given in line with the standardisation used previously, and the title was given separately in the archival record, the Edo title was added as a title. For example, an individual with the name Alohan Odigie was recorded as being an Odionwere in an archival document, so his name was included as ‘Odigie, Alohan’ and ‘Odionwere’ was added as a title. This is just a starting point for future research, and until now only very limited changes were made to the spellings; when changes were made, it was only to bring the orthography in line with that used elsewhere on the platform.

The work done to identify names is only in the beginning stages, and more research is necessary to identify individuals, biographies and provenances. In this early phase, Digital Benin researchers were able to add a further 892 names, bringing the total to over 2,000. The names identified in the archival and photographic documents indicate the identities of organisations, institutions, societies and individual people.

The term ‘actor’ is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary (2023) as ‘a thing which or person who performs or takes part in an action; a doer, an agent’. The project team used this term to describe the organisations, institutions, societies and people whose names were identified in the archival and photographic documents and who participated in various ways in the lives of the royal treasures from Benin Kingdom. Certain people, companies and societies may have been involved in the physical movement of the treasures, while others may have participated in the purchase or sale of treasures. Others may have played a role in how these treasures were understood or researched, and therefore we include active, participating and facilitating actors in the identified-names list. The network of these actors produced through the identification of these names in archival material can be viewed in the Actor Network Explorer.

Identifying Accession, Collector and Other Numbers

Webster Numbers

William Downing Webster, like many collectors and dealers, attributed numbers to objects he bought and sold. These numbers are sometimes known colloquially as ‘Webster numbers’ and are four or five figures in length. They were attributed to objects as they came into his possession, and recorded in stock books and on the objects themselves (for example, see figure 1). In addition to the Webster number, typically a brief description of the object was included in the stock book along with the price it was purchased for and details of whom it was acquired from. These stock books are held at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and have been digitised with funding from Digital Benin.

Figure 1: A screenshot of the Digital Benin catalogue showing an Ama (Af1944,04.9). On the left, a handwritten Webster number in white ink can be seen on the back of the object; on the right, the Webster number is circled in the object metadata.

In addition to stock books, Webster produced thirty-one illustrated sales catalogues between 1895 and 1901. These catalogues include drawings and photographs of objects Webster owned and had for sale, brief descriptions of the objects (typically one line) and the numbers Webster attributed to the objects. Often these catalogues were distributed by Webster to museum curators and collectors so they could choose which objects to purchase. The catalogues were later bound into five volumes and published as Illustrated Catalogue of Ethnographic Specimens. The Wellcome Collection and Library recently digitised and made all five volumes available online.

These stock-book catalogues have proved to be a key resource for researchers of the provenance of objects from the Kingdom of Benin. The illustrated catalogues are a particularly useful resource due to the depictions of the objects, which offer a valuable opportunity to visually check if an object matches the Webster number. However, Webster also bought and sold objects which were not included in these catalogues, therefore the stock books, which seem to include a greater number of objects which passed through Webster’s hands, provide a more comprehensive list for researchers to check, albeit without photographs of the objects.

Both the stock books and the illustrated catalogues have been added to the Digital Benin platform and were tagged using the system described above. In order to tag specific objects from the Digital Benin catalogue, the objects needed to be identified. Fortunately, many staff members of institutions that have or had objects in their collections were aware of these numbers, and have recorded them in the object metadata in the Digital Benin catalogue. Imogen Coulson was able to search for numbers in the catalogue and, after cross-checking these against the descriptions and, when possible, the images of objects, link the number in the archival document to the object in the Digital Benin catalogue.

Over the past two years, several institutions have been conducting provenance research into the objects in their collection from the Kingdom of Benin. Webster numbers did not always appear in the object data in the catalogue, but researchers have been able to identify these numbers in reports published from this research (e.g., Hans et al. 2021, Hertzog & Uzebu-Imarhiagbe 2023, Bedorf 2021). Imogen Coulson also went through these reports to check if there were any further objects which could be linked to Webster numbers mentioned in the archival documents.

Wellcome Numbers

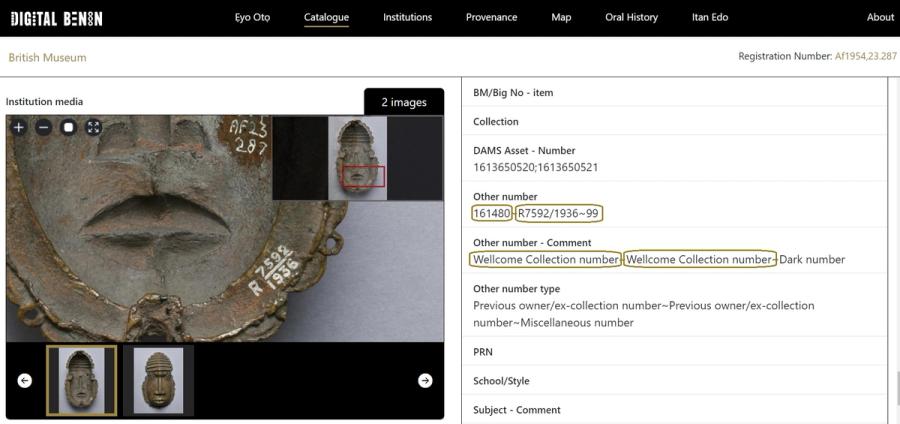

Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome was a collector who amassed millions of objects during his lifetime. These objects, which were acquired both by agents in the field and at auctions in London, were given numbers upon their accession by the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum (WHMM), which, from the 1920s onwards, was recorded on a ‘flimsy inventory card’. The numbers attributed to objects are sometimes known as ‘Wellcome numbers’, much like the ‘Webster numbers’ discussed above. As different numbering systems were used by the WHMM staff, these vary in their format. Typically, Digital Benin researchers found that five-figure numbers were more commonly used in the object metadata in the catalogue, whereas Wellcome numbers beginning with ‘R’ were more frequent in images of objects (figure 2).

Figure 2: A screenshot of an Uhunmwu-Ẹkuẹ (Af1954,23.287). On the left, a handwritten Wellcome ‘R’ number can be seen in white ink; on the right, the two different Wellcome numbers have been circled. The first is a six-figure number and the second is the ‘R’ number, also seen on the Uhunmwu-Ẹkuẹ.

A report from Hugh Nevin Nevins includes photographs of objects he collected for Wellcome in 1936. Wellcome numbers are found throughout the report: at the beginning, the range ‘59006–59284’ has been handwritten, and small labels with handwritten five-figure numbers can be seen attached to objects in the photographs. Imogen Coulson was able to search for these numbers in the catalogue and, after checking them against the photographs, link the object records to the archival material.

Relief Plaques: Foreign Office Numbers, Read and Dalton References, and Numbers on the Plaques

The research team are continuing to identify and match these numbers to records in the catalogue as well as research the different numbers visible on the front of Ama. This is an ongoing process and will continue alongside research into the historical objects.

Conclusion

Digital Benin developed the archival explorer and its tools and access points with these two aims:

- to enable users to explore the material across institutional collections;

- to link archival material with research and object data included on Digital Benin.

This time-intensive process is critical to improving the ways in which users engage, search and explore the digitised material we brought onto the platform. Recognizing that archival and photographic material is dispersed among different institutions, we created a valuable tool that gives our users the ability to search this varying material in all the collections and in connection with its object data.

Bibliography

Hans, R., Lidchi, H. & Schmidt, A. (2021). Provenance Vol. 2: The Benin Collections at the National Museum of World Cultures (F. W. Veys, ed.; vol. 2). Sidestone Press; National Museum van Wereldculturen. https://issuu.com/tropenmuseum/docs/2021_provenance_2__benin__e-book.

Hertzog, A. & Uzebu-Imarhiagbe, E. (2023). Collaborative Provenance Research in Swiss Public Collections from the Kingdom of Benin. https://rietberg.ch/files/Forschung/Benin-Initiative/Bios-Statements-Photos_Nigeria-Delegation_Feb2023/20230202_BIS_report_def.pdf.

‘actor, n., sense 3.a.’ (2023). In Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/5929114494