Ẹyo Otọ

Ẹyo Otọ is a learning space about the objects and their Edo designations. Listen, view and read about their use, production and function.

Catalogue

Search, filter and explore data, images and linked research for 5,285 objects from 137 institutions in twenty countries.

Institutions

View objects listed in the 137 institutions in twenty countries currently holding historical Benin objects in their collections.

Provenance

Study the roles, biographies and object relations of provenance names found in the information provided by 137 institutions.

Map

Explore a present day map of Edo South (ancient Benin Kingdom) and Benin City. See the current location of the historical objects worldwide.

Oral History

Listen to oral traditions Benin people share, to transmit and preserve knowledge and cultural traditions from one generation to another.

Itan Edo

Itan Edo is the story of Benin Kingdom. Read about the cultural and historical trajectories related to kings, queens, guilds and more.

Archival Documents

Access the digitised archival documents that relate to the historic Benin objects, their provenance stories and the wider history of Benin Kingdom.

Archival Institutions

Explore a source guide of institutions that hold archival material related to the Benin Kingdom, its history and the objects shown on the platform.

Digital Research Tools

Study data on the platform with digital research tools and visualisations.

About the project

Ẹyo Otọ

A small number of Aga, European-style chairs with backs and armrests, are part of the corpus of objects made from wood. As a material, wood was not typically controlled by the Ọba the same way ivory and brass were. It is therefore difficult to say who may have commissioned, used or owned these chairs.

The Ahianmwẹ-Ọrọ, meaning ‘bird of prophecy’ in English, is a bird with a long beak, the cry of which is said to be prophetic. If it cries ‘OyaO’ (disgrace), it portends danger or disaster. If it cries ‘Oliguegue’ (be grateful), it portends good favour, fortune or luck. If it persistently cries ‘OyaO, OyaO’ in front of someone, it is prophesying that the person should be cautious and should not undergo a journey or should return home rather than continue on. But if the bird cries ‘Oliguegue’ continuously, the journey will be favourable. The bird is believed to be a messenger of the spirit world.

Aken’ni Elao (altar tusks) are usually ivory tusks carved with scenes of ceremonies or spiritual activities. These were placed at the ancestral shrines of the Ọba and were primarily made as a historical record for documenting events. For the Edo people, the white colour of ivory represents the purity of spirituality. The Ọba owns one tusk from every elephant killed by right and reserves the right to buy the other one. Aken’ni Elao are placed in the opening in commemorative heads at the ancestral altar.

Akhẹ-Osun (Osun pot) is a specific term for the pot used for storing medicinal plants at the Osun Shrine. Akhẹ-Osun can be distinguished by the high-relief decorative motifs around the rim of these pots, which are often figurative. The motifs depend on the deity at whose shrine the Akhẹ-Osun was used for medicine. We have Akhẹ-Osun Ake, Akhẹ-Osun Ebomisi, Akhẹ-Osun Olokun, Akhẹ-Osun Oghidian and many other deities.

Ako-Ọpia (sheaths) are covers made from leather or other materials. They are used to hold or protect any kind of bladed weapon, such as Idẹnrhẹn, Umozo or Ọhọ. A number of these are heavily ornamented and cast in brass and have ceremonial and practical functions. They are used to hold sharp blades or keep blades in a safe place by warriors, and executioners, while during burial or funeral, the heir to the deceased wears a leather Ako-Ọpia. A smaller number are made from coral beads, which are used by the Ọba during royal ceremonies.

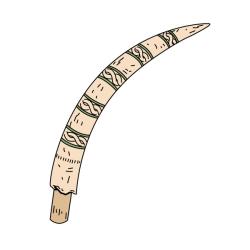

Oko are side-blown horns and Akohẹn are flutes, however since the instruments look very similar they are grouped together here. Oko are frequently used by priests to evoke spirits and by traditional doctors to drive away witches when attending to a patient that may have been afflicted by a witch. Oko can also serve as an object of commemoration; when a new Ọba sends an ivory Oko to be kept at the Olokun Shrine in Ughoton, it is to commemorate his accession to the throne. Akohen, on the other hand, is a flute. Egharevba (1968:40[7]) dates the Akohen to the era of Ọba Eresoyen.

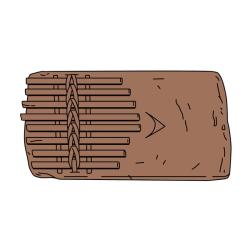

Akpata (bow lute) is a harp-like instrument made of wood and strings which makes a sound like a guitar. They continue to be used for entertainment during special festivals and ceremonies. Historically, the Akpata was one of the key musical instruments alongside the Asologun played by Edo musicians to accompany narrators during storytelling (Ben-Amos, 1975, p.25[41]).

Ama is a pictorial combination of figures that has a historical explanation or is a visual representation of a historical event. Ama had a mnemonic purpose, aiding one to recall the events or persons represented in the artwork. Benin oral traditions are popularly transmitted in the form of commemorative festivals, stories, plays, songs, poems, riddles, proverbs and other forms of oral literature. Ben-Amos (1980:28) observed the existence of over nine hundred known plaques which provided a testimony to court life at the time of Ọba Esigie, considered ‘a sort of pictorial record of events in Benin history, an aid to memorizing oral traditions’.

Anwa and Akpoka (tongs) were used by members of the Igun-Ematon and Igun-Eronmwon (Dark, 1973 ,p.48, 55[61]). Today they are still used by members of the Igun-Ematon to handle hot objects, such as crucibles, during the casting process.

Aro Ododua are ritual masks that have two forms: male – Uwen – and female – Ọra. According to oral tradition, when Ọranmiyan left Uhe, he brought two totems, Uwen and Ọra. The male is identified by the four suborbital marks that identify a Benin man. Uwen guarantees that the Ọba survives at war, no matter how terrible the war is. Ọra guarantees the productivity of the Ọba, as he must always have children. They are also known as the two royal deities – Ẹbọ n’ẹdo. They can only be produced by guilds when commissioned by the Ọba.

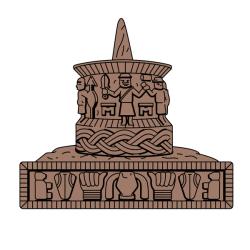

Asẹbẹrhia (altar rings) are displayed on ancestral altars dedicated to the Iy’Ọba, as she was usually entitled to one. Just like the Ọba, after her death an altar in her memory was erected within the palace and decorated with a collection of objects related to her achievements in life. The Asẹbẹrhia usually consists of figures around a principal figure with a circular base. They are made by the Igun Eronmwon.

Ebẹn are often described as swords, however they are used more like sceptres. During ceremonies titled chiefs would hold them or throw them during dances, and in doing so they pay homage to the Ọba at these public events. When a chief receives a certain status and is awarded an Ebẹn, he would dance with it to pay homage to the Ọba. It is forbidden for Ebẹn to touch the ground, so the chief would have to take extra precautions to avoid dropping the Ebẹn during the dance. Therefore the Okae-Odionmwan (head of executioners) dances with the cutting sword (Umozo) behind the dancing chief.

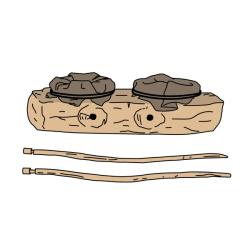

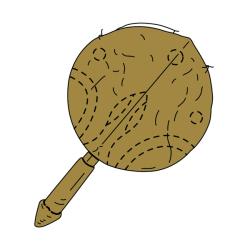

Ekuẹ (bellows) are used to blow air into the fire or furnace, increasing the temperature for brass casters in the Igun-Eronmwon and blacksmiths in the Igun-Ematon. Ekuẹ would be pumped by hand using two attached poles. Hand-pumped bellows were used by the brass casters until 1998, and now battery-operated furnaces are used (Nevadomsky, 2005, p.75[92]; Kalilu & Emeriewen, 2015, p.72[221]).

Elubasẹ are a type of Eguen, an anklet which has integral rattles. The rattle pellet is made from fibre originating from the Urua palm (Borassus flabellifera). Each rattle is about 5 cm in diameter and contains two or three Esalobo grains. According to oral tradition, Eguen anklets were introduced into Benin by Ogiso Ere in the tenth century. Elubasẹ are worn by children as a way to track their movements.

Every drum can be divided into subcategories. The kettledrums (Obiza) consist of a clay pot whose opening is covered with the skin of a viper – the skin is both tied with a cord around the neck and also braced through holes in the edge of the skin with laces which are tied to another cord at the bottom of the pot.

Emwiokọ is the term generally used in Edo to describe plants and young crops and is therefore used to designate objects described in English as plant specimens. The examples shown here were collected by Northcote Thomas during his time in Benin City and the surrounding areas. Although not typically an art of the royal court, these were collected prior to the 1930s and have thus been included in this catalogue.

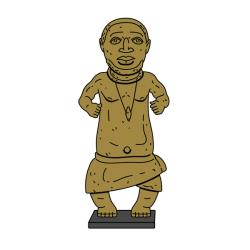

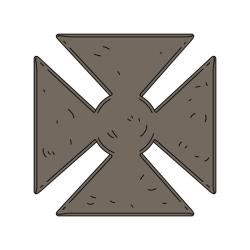

Ewua is the title of a priest belonging to the Holy Aruosa Church, also referred to as the church of the Ọba of Benin. The church was first established by Portuguese missionaries in the fifteenth century. Each morning, noon and evening, the Ewua priest goes to the Ọba to lead prayers or devotion (this is an indication of the Catholic culture of the Angelus at 6:00 am, noon and 6:00 pm). The bronze casters today say that the figure holds an Avan, a small axe, in their left hand, though European literature refers to it as a hammer. He is also depicted wearing the equal-armed or Maltese cross on his chest.

Ẹguẹn are worn by the Ọba and chiefs as part of their Ehaengbehia, the full regalia worn during special ceremonies. Ẹguẹn are worn around the ankles or calves and can be made from beads, ivory, brass or even iron. A separate category, called Elubase, refers to those which have integrated rattles or crotal bell attachments, however both are described as anklets in English.

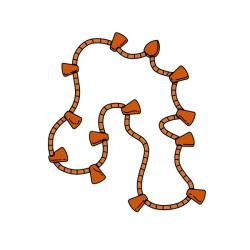

Ẹkan are beads made from the semi-precious agate stone. They look similar to the beads known as Ivie, which are used to make jewellery. However, Ẹkan are more greyish in colour and are of less value than Ivie. The Ọba in the past would control both Ivie and Ekan and one could only wear them if the Ọba gave the right to do so.

Ẹkpẹn (leopard figures) are widely featured in Benin arts. In Benin, leopards are considered the king of the forest and as such seen as a symbol of authority. The leopard is a royal symbol of kingship because it embodies the qualities of courage, strength, ferocity and wisdom. Leopards were hunted by Iviekpen.

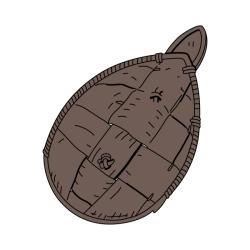

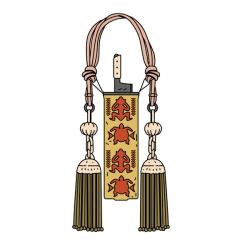

Ẹkpoki were often made by the Isekpokin from leather, however the Igun Ẹronmwon made some from bronze. They would have been used to carry precious and important objects to the Ọba and, according to oral tradition, the heads of conquered enemies, soil taken from conquered lands and beads. Ẹkpoki may also have been used for the storage of the Ọba’s ceremonial clothes.

Ẹrhẹ are round stools with two intertwined serpents as the supporting column. Aside the two serpents, which point in two different directions (up and down), other creatures such as frogs, leopards, roosters and human figures are seen on these stools. The Obah n’uhi pattern of design (which has no beginning or end) is seen at the top of these stools, which shows the supremacy of the Ọba (king/emperor). These are ceremonial stools used by the Benin chiefs when performing rituals in ancestral shrines. According to oral tradition, Ogiso Ẹrhẹ was the first to use a throne.

Ẹrhu describes different items of headwear which may be worn by chiefs, priests or the Ọba himself. The coral crown, or Ẹde, is for the Ọba only, while red hats made from Ododo fabric are a part of the pangolin ceremonial dress, or Ekhui, worn by chiefs. The cowrie-shell crown was worn by Ogisos and introduced by Ogiso Ẹrhe.

Ẹzuzu (fans) were particularly important when it came to the comfort of the Ọba and other high-ranking individuals, such as the Iy’Ọba. In the past, at least two servants were always with the Ọba to fan him, although today the use of fans is more symbolic. Some fans were specially decorated with mirrors and used specifically by Olokun devotees. Fans are usually made from skins, antelope or cow, with embroidered appliqué designs made by the Isekpokin (Roth, 1903, p.123[95]). Highly decorated fans were used by the Ọba and chiefs, and fans made from leopard skin with certain patterns were made only for the Ọba.

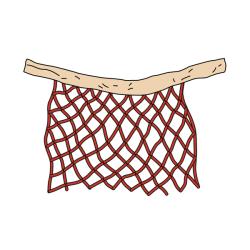

Ifẹnmwẹ (arrows) were usually used alongside Uhambọ and Ẹkpede. Ifẹnmwẹ were part of the weaponry used for hunting animals and during warfare. The shaft was a product of the Igbesamwan guild, and the tips were made by the Igun-Ematon. Ifẹnmwẹ tips could be dipped in poison made by the Ilobi, who still continue to make toxic substances.

Igho (manillas) translates directly from Edo to mean ‘money’, and as manillas were a form of exchange in the past, they were and are called Igho. Igho were the principal currency used within southern Nigeria during the Ọba dynasty. The British attempted to end the use of Igho with the Native Currency Proclamation of 1902, which prohibited the import of Igho with the aim of encouraging the use of coined money. However, Igho continued to be used, and in 1948 the British undertook a major recall dubbed ‘Operation Manilla’ to replace them with British West African currency. In contemporary Nigeria, images of Igho can be seen on the 100 naira banknote, illustrating their continued importance as a symbol of money and wealth.

Obọ, the hand or arm, is recognised to be the seat of power of accomplishing things. Its worship is specific to warriors as well as wealthy and high-ranking people. It is worshipped to ensure success for special undertakings and give thanks. The Ọba and some people of high rank still have special altars of the hand, called Ikẹgobọ, which take the form of sculptured cylindrical objects in wood, or occasionally bronze, depending on the status of the sponsor.

Ikoro are big wrist bands made from different materials like brass, ivory and wood. They are worn by the Ọba and chiefs during ceremonies when dressed in their full regalia. They could be made by different guilds depending on the material used – the Igun Eronmwon would make them out of brass and bronze while the Igbesamwan would produce ivory and wood Ikoro.

Ikpin (snake figures) featured on the roof of Ọba Palace. In the Kingdom of Benin, the crocodile and the boa constrictor are considered the guardians of Olokun, the god of the great waters or the ocean, of wealth, prosperity and fertility. When the palace was burnt down during the 1897 British expedition, the Ikpin were stolen, and they do not feature on the roof of the current palace.

Isanrẹn can be used to lock up rooms such as the aza emwin arhe. This is a vault or a storage room for valuables, for example money, ivory, artifacts, coral beads and clothes. Isanrẹn were cast in brass, which indicates that they were used within palaces. Others were made in a combination of iron and brass and would have been produced by both the Igun-Eronmwon and the Igun-Ematon. Some pieces may include coral or agate inlays, suggesting they would have been particularly important and possibly used only in Ọba Palace.

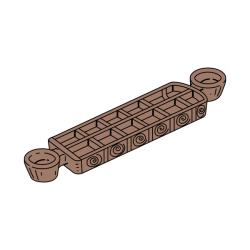

Isẹ (game) describes any kind of game being played for entertainment, from a board game with pieces to a puzzle or card game. A common game played in Benin is called Ogirhise, however a single wooden game is included in the institution holdings shown here. Two people would play this game with small stones or smoothed seeds.

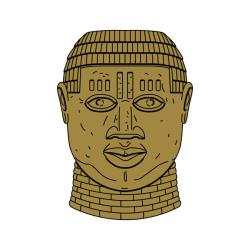

Ivbiotọ (trophy heads) are thought to represent decapitated heads of former Benin vassals who rebelled against the Ọba. When a rebel vassal was defeated, his head was removed and brought to Benin in an Ẹkpoki. The Ọba sent it to the Igun Ẹronmwon, where they made bronze replicas. The three Udari, or suborbital markings, show that the image is that of a non-Benin male.

Onwọ directly translates to ‘beeswax’ in English and can be used to describe the wax model made by brass-casters. It is an essential material, because when heated the Onwọ melts and creates a vacuum for the molten bronze or brass. Onwọ can refer to bees and honey as well. In contemporary Benin City the brass-casters sometimes substitute Onwọ with candle wax. However, Onwọ cannot be totally replaced in this process, and the brass-casters confirm that some works could only be designed using Onwọ.

Osisi (gun) and Etu (canon) are both types of firearms. Although the Portuguese developed trade and alliances with Benin Kingdom from the late fifteenth century onwards, a papal ban on the sale of firearms to non-Christian peoples prevented firearms being sold to the Ọba (Ryder, 1969, p.41[112]). Despite this prohibition, some firearms did make their way to Benin Kingdom by the end of sixteenth century, and as other European powers such as the Dutch traded with the Ọba, different firearms were acquired.

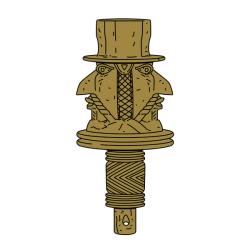

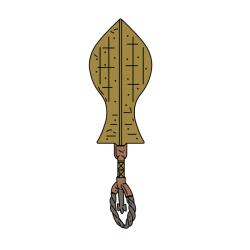

Osogan (Osun staffs) are kept by the Osun priests, and they were usually fortified with medicine. Osun is the deity of medicine and ensures the effective use of all forms of medicines, curative or otherwise. Osun is worshipped by the professional traditional doctors called Ewaise, and their guild performs an annual festival called Ehosun in honour of the Osun deity. During the festival, medicines are believed to be strengthened, and the Osogan can stand without support, exhibiting mystic powers. Osun can also be worshipped domestically. Households with Osun shrines have special rooms where their medicine is kept, and annual rites are performed. Different priests have various ornaments on their Osogan which usually represent the powers they have attained – when a priest acquires or attains a certain power, he adds a representation of this power to his Osogan. This makes every Osogan different.

Ovazẹ (anvils) are used today as chisels by members of the Igun-Eronmwon and Igbesanmwan to carve wood or split smaller pieces of wood. Despite the similarities in the ways they are used, Ovazẹ were identified separately from Afian (chisels) by members of the Igun-Eronwmon. In literature written by European scholars during the twentieth century (e.g. Dark, 1973), these objects were described as anvils, and they were part of the core assemblage of tools used by blacksmiths of the Igun-Ematon (Dark, 1973, p.55). It is possible that the ways these objects have been used has changed over time, or they were used differently by members of the Igun-Eronmwon and Igbesanmwan.

Bronze cock which did not come into existence until after the introduction of the Iy’ọba title by Ọba Esigie. The first Iy’Ọba was Idia, and the Iy’ọba title is considered to be the greatest achievement of a Benin woman. It has spiritual significance and is placed at the altar of the Iy’ọba after her death. The Iy’ọba is referred to Ọkpa n’ Uselu (Ọkpa being a shortened version of Ọkporhu).

Ugbẹkun (girdle) is the literal translation for ‘objects which are tied around the waist’. Ugue-egen is another word which can be used to describe a girdle-like object. These may be worn by the Ọba or chiefs either underneath or on top of clothing. When underneath, medicine or potent charms may be added for protection. When worn over clothing, pendant masks may be hung from the girdle. Included in the institution data is a leather object called Akpalode, which is a girdle produced by Isekpokin, the royal leather workers, and is infused with herbs and medicine worn by warriors for protection. Also included in the institution data is an object known as Ukugbohamwen, which is worn by the Ọba and the great chiefs during ceremonies. When Ukugbohamwen is worn the Ọba does not feel hunger, and it is believed that he could wear it for two weeks without food or drink.

The Ugbudian (flywhisk) is one of the four items (Ada, Eben, Oro and the Ugbudian) that must be given to a prince when he is sent to establish a new dukedom. Made from leather, Ugbudian is harsher than the other type of flywhisks made from horsetail hair. It is used to chase the tsetse fly. This type of flywhisk could also be made from materials such as coral beads, however the coral flywhisk would have been used in ceremonial contexts.

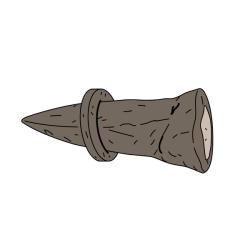

Ughavan (celts) are thunderbolts or stone axes usually found on Osun altars. They are obtained by pouring four tins of oil into the hole in which the Ughavan landed when falling from the sky as thunderbolts. Uloko (Iroko) is said to be the only tree that can withstand Ughavan while other trees shatter. According to oral tradition, Ughavan is believed to be thrown by Ogiuwu, king of death, also known as god of thunder.

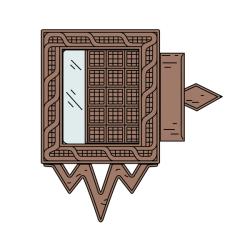

Ughegbe (mirrors) are encased in carved wooden frames with a sliding wooden panel that would cover the glass when not in use. The wooden frame was carved by members of the Igbesanmwan, while the glass for the mirror would have been one of the goods traded to Benin by European merchants. Ughegbe were used mainly by priests and are viewed as portals to see beyond the physical world. They would be covered when not in use to prevent entities from the spiritual world entering the physical world where they do not belong.

Uhunmwu elao ọghe Iy’ọba (commemorative queen mother heads) were placed at the ancestral shrine of the Iy’Ọba. Similar to the Ọba’s altar, the Iy’ọba also had an altar erected on her behalf which consists of a commemorative head. The Uhunmwu elao ọghe Iy’ọba are particularly distinguished by the Upkẹ okhokho (chicken beak) hairstyle. Usually, a woman in Benin would only have three suborbital markings, however the Iy’Ọba is shown in many of these objects with four suborbital markings, which would usually indicate a man. This may indicate thato when an Iy’Ọba is crowned, she ascends to a status usually belonging only to men.

The commemorative head, Uhunmwu Elao, of an Ọba placed at the king’s ancestral shrine could be made from bronze, wood or terra-cotta. The altar consists of a commemorative head that supported the carved ivory tusk. It could have a circular base or a rectangular-shaped base. However, they all have a unifying feature, which is the hole at the centre in which the tusk is placed.

Ukeke (strikers) are used with other instruments, in particular gongs but also some drums. They are carved from tree branches and are most likely produced by the Igbesamwan. Interestingly, in comparison to gongs and drums, there are relatively few strikers known today in institutional collections.

The Ukhuerhe (tables) shown here bear a similarity with other carved objects because they are highly decorated and record events that took place in the Kingdom of Benin. Because they document events through these carvings, the could be called Ama. However, in Edo tables are called Ukhuerhe, so we have used this term here. The Ukhuerhe shown here are produced by the Igbesamwan. Although variable in size, shape and age, they all feature carved motifs on the upper surface of the table-top and in some cases on the legs.

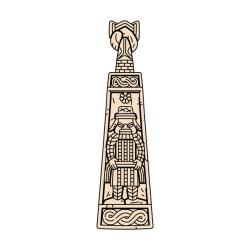

Ukhurhẹ are placed at the ancestral shrine of each family. A carved wooden staff is placed in honour of the first son, and his achievements in life are carved on it. Ukhurhẹ reflect the activities of generations of elder sons. When the paternal head of a family passes away, an Ukhurhẹ is commissioned by the new head of the household and carved by a member of the Igbesamwan to commemorate the deceased, and an Ukhurhẹ is added to the family’s ancestral altar as part of a ceremony.

Ukpọn (clothing) can be made from many kinds of textiles, from woollen aprons to cotton cloth. In the past, only a few colours were used in the production and dying of textiles, which may explain why only red, blue and white are seen in the clothing grouped together here. Blue would have been made from indigo, whereas red would have been from ume or camwood.

Ukpu (cups) included in the catalogue are made from brass, bronze, wood or ivory. Some are decorated with human figures and others have pedestals or feet, similar to a chalice. Those in brass and ivory would have been mostly used in the royal court, as the possession of objects made from these materials was restricted to the Ọba and some chiefs who obtained certain ranks in palace societies.

Uman-ague and Ugbugbe are two different kinds of crosses. Uman-ague refers to the equal-armed or Maltese cross, and Ugbugbe is used to describe the Christian cross, which has a longer vertical axis. Uman-ague is a symbol associated with the Holy Aro Osa Church. According to oral tradition, the Uman-ague can be given to a chief who has passed through the Ague fast or who has been in the team that went to Ẹguae-Oghene, which is located a journey of about six hundred days away from Benin City, although the exact location is not known today. Upon reaching Ẹguae-Oghene, the team would have to meet the Oghene, a religious leader. However, the Oghene cannot be met face to face and stays behind a curtain when meeting with visitors. He can only reveal his big toe, which is red, to prove his existence. When the chief returns to Benin, he is answerable to only the Ọba and no other.

Ọhọ is the executioner’s sword, and it is one of three items given to a prince being sent out to establish a dukedom. This gives the prince the power of life and death. The blade and part of the handle is iron, and the top of the handle is brass. Both the Igun-Ematon and the Eronmwon would have made this object. During ceremonies the Enogie, a duke, rarely brings out the Ọhọ, which is used by his executioners. While the Umozo, which is the cutting sword, is used during wars. In contemporary times this is used ceremonially and during the Isiokuo festival, which is more like a victory parade.

Umọmọ (hammers) that are part of the institution holdings have a distinctive L shape. They were used by members of the Igun-Ematon, Igun-Eronmwon and Igbesanmwan. The hammer is made by members of the Igun-Ematon as it was made with iron. Ewua messenger figures are also depicted holding this hammer in their left (proper) hands.

Urhotọ (altar tableau and altar rings) are displayed on an ancestral altar dedicated to the Iy’Ọba, who was usually entitled to an Urhotọ in her ancestral shrine. Just like the Ọba, after her death, an altar was erected in her memory within Uselu Palace and Ọba Palace. These altars would be decorated with a collection of objects related to achievements in life.

Urhukpa-Ẹvbi (lamps) means ‘oil lamps’, and they are used to illuminate the house after dusk. Most lamps were made to have a curved plate-like bottom in which the oil would be poured and lit, and they are hung from chains attached on three or four sides. The Urukpa-Ẹvbi would be made with iron by the Igun-Ugboha, who are part of the Igun-Ematon and are responsible for producing household items.

Ẹgba (bracelets) are worn as part of ceremonial costumes and could be made of brass, bronze, iron, ivory or wood. The material determines the status of the individual wearing it, as the Ọba controls the use and production of brass, bronze and ivory. Ẹgba is the designation used to describe bracelets worn around the upper arm that could potentially become amulets by putting charms or medicine in them.