Date of document publication: 2022-11-07

Introduction

Digital Benin assembles object data and related documentation material from collections worldwide and provides a long-requested overview of the objects looted by British forces from Benin City in February 1897. In doing so, Digital Benin forms a well-founded and sustainable catalogue of the artworks and their history, cultural significance and provenance. The first step in forming this comprehensive overview was to develop a set of guiding parameters (see below) which could be shared with institutions, acting as the basis for discussions around the project and its scope, and providing a foundation for museums to share data with Digital Benin. Once data had been shared, a review process (see below) was developed by the Digital Benin principal investigators and team members, namely Prof. Dr. Barbara Plankensteiner (PI), Prof. Kokunre Agbontaen-Eghafona (PI), Dr. Felicity Bodenstein (PI), Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie and, from October 2021, Imogen Coulson.

Digital Benin builds on a legacy of research, in particular Felix von Luschan’s (1919) Die Altertümer von Benin, an early printed catalogue of the objects held in German collections; Philip Dark’s (1982) An Illustrated Catalogue of Benin Art, which built on years of research into both private and museum collections worldwide; and Barbara Plankensteiner’s Benin Kings and Rituals; Court Arts from Nigeria (2007), as well as private research lists from the principal investigators. However, in the years since the publication of these works, objects have continued to circulate, and today some are located elsewhere. More recent research (e.g. Hicks, 2020) collated a list of public institutions, though without including the objects themselves. Many of these books are out-of-print, often only accessible in libraries and expensive to purchase secondhand. They were also written for researchers and scholars rather than a general audience. These publications laid the foundation for the Digital Benin catalogue, however there was a need for an up-to-date and more extensive overview of Benin holdings in institutional collections. Digital Benin aimed to address these needs, putting together a catalogue of objects that had not existed before. The approach taken by Digital Benin to contact institutions with the request to transfer all information digitally stored in their collection-management databases and archives about the Benin objects and then to digitally assemble and present the information on an online platform is a novel one which speaks to a much wider discourse in museology and restitution debates.

The request to assemble the historical Benin objects online required a data-review process because it became evident early in the project that some institutions did not have the staff available or capacity (especially during the lockdowns of the coronavirus pandemic) to review the data preliminarily transferred to Digital Benin. We asked the institutions to send us as much as they could, and consequently organised a workflow for the data review. Digital Benin recognises the importance of openness and transparency regarding the entirety of this review and research process. Thus, the steps involved are outlined in detail below.

Guiding Parameters

In 2019 and 2020, the Digital Benin principal investigators (PIs) developed a set of guiding parameters which were shared with institutions beginning in late 2020 in introductory calls, emails and online meetings in which the institutions were also invited to participate as partners in the project. The parameters explained the scope of the project and detailed the kinds of objects which were of interest.

The scope of Digital Benin is centred on those objects looted by British forces from Benin Kingdom during the British military invasion in February 1897. Many of these objects are described as ‘royal art’ and/or ‘court arts’ in literature and scholarship of the twentieth century (e.g. Blier, 1998; Freyer, 1987; Kaplan & Shea, 1981, Plankensteiner, 2007). Therefore, the primary focus was to gather data relating to objects made and used in Benin Kingdom until 1897. In recognition of the fact that this corpus is not clearly defined, the parameters were expanded to consider any objects related to the kingdom that were created and/or circulated from the African continent to Europe or North America from 1897 to the 1930s. These objects form the ‘core’ of the Digital Benin dataset.

A second, more broadly defined aspect included objects which tell ‘relevant stories’ and offer insights into the ‘core’ dataset. ‘Village-style’ objects, ‘Bini-Portuguese’ ivories or ‘Udo-style’ objects were offered as examples.

Information regarding relevant archival and/or historical materials dating to the period from the 1890s to 1930s was also requested. Examples provided were field notes, photographs, postcards, correspondence and further provenance materials. We also requested digitised copies of these archival materials if they were available.

Using this set of parameters, Digital Benin was able to form a wide-ranging understanding of the holdings in institutions worldwide. From here, the team could identify which ‘relevant stories’ most clearly related to the scope and aim of the project and review the associated objects. Through these parameters, we hoped to accommodate the institutions involved, each with their own expertise and resources relating to these objects.

An initial deadline to share data was set for October 2021, with updates possible until May 2022. In practice, this timeline was stretched by some institutions, and additions to data were received until August 2022. Many institutions have been actively researching objects and the provenance of Benin objects throughout the period we have been developing the platform. Thus, there was a need to be flexible in response to these developments. The Data Acquisition and Data Management documentation provides more detail on how data was acquired and managed by Digital Benin.

Review Process

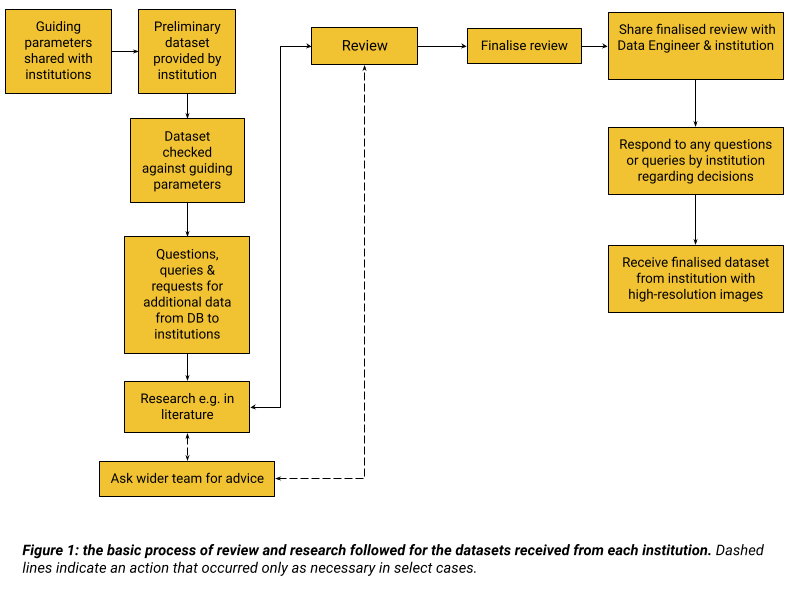

Once institutions shared preliminary datasets with Digital Benin, members of the team (detailed above) reviewed and researched them to decide which objects to include in line with the guiding parameters outlined above. Each institution provided datasets in a different format, from spreadsheets, PDFs and Word documents to JSONs, emails or simply links to their online collection. Images of objects were often provided separately to the data, requiring the initial work of matching object data to images. Additionally, the data itself was variable – sometimes a large number of high-quality images and detailed provenance was available, other times there was only a single image or none at all and no provenance information, not even a date of acquisition by the institution. Therefore, each dataset had to be assessed and researched individually. A flowchart representing the basic process followed for each institution is detailed below (fig. 1).

The first step involved looking through the datasets to identify objects which could easily be identified as lying outside the remit of the project. A common example was objects from the Republic of Benin (the country located directly to the west of Nigeria), rather than the Kingdom of Benin (located in present-day Nigeria). Additionally, as the production of objects by guild members in Benin City continues today, there are several objects in museum collections which were produced after the 1930s. Except for artworks with a named artist in the institutional data, the objects lay outside of the project’s remit, so careful attention was paid to identify these where possible. At this point, if additional information and/or images were required to advance the review, this would be discussed with the institution. In some cases, it was not possible to receive additional information, and so a review had to be done based on the information provided. Often discussions with members of staff at institutions, particularly to ask for more information regarding provenance and additional images, were necessary. We aimed to ensure the process was a dialogue with curators and collection management staff, using the review process as an opportunity to share knowledge.

The second step involved a more detailed assessment of the remaining objects. This involved looking at the data to assess whether objects fit the parameters described above. The variable nature of the datasets required the necessary, albeit complex, task of weighing different kinds of information and treating objects, when time allowed, on a case-by-case basis. Dimensions and weights were useful alongside images, as these helped build a better understanding of the objects and enabled comparisons between similar types of objects. For example, it was useful to check the dimension of relief plaques, as these normally fit within a narrow range for wide and narrow plaques, respectively, as identified by Kathryn Wysoki Gunsch (2017, p.122, n30[24]). Additionally, photographs of both the front and back of an object with enough definition to see the iconography and decorative motifs were useful. This could assist with the identification of additional museum or collector numbers which could help to confirm the provenance of an object.

Supplementary research conducted by the team was necessary to further assess whether objects should be included. For example, crosschecking the presence of objects in catalogues and publications helped to confirm whether an object had been part of different collections, and thus the provenance of an object helped to make these decisions. Sometimes this also provided additional and comparative images which were useful for reference, such as early catalogues like Augustus Pitt-Rivers’ (1900) Antique Arts from Benin. More recent catalogues also proved useful, for example Ezio Bassani and Malcolm McLeod’s (1989) catalogue of the Jacob Epstein collection, which contained pieces from Benin which were auctioned off after Epstein’s death in 1959. Through this catalogue, we were able to confirm that an Ada (AO 785) now in the collection of the Museu Nacional de Etnologia in Lisbon had been part of the Epstein collection, thus extending our understanding of the provenance, which supported the decision to include the object in the catalogue. The amount of supplementary research that could be carried out was limited owing to the tight timeline of the project and was reliant on the expertise and knowledge of the PIs and project team. A long-term research project and ongoing study of the translocated objects in institutions worldwide has great potential to develop and expand these insights.

Several additional resources were also critical in the review and research process (see Bibliography and Zotero group library). Recent provenance reports carried out by museums also assisted this process (e.g. Bedorf, 2021; Hans, Lidchi & Schmidt, 2021; Hicks, 2021). Many publications which were necessary for the review process are not available online or on open-access platforms. Knowledge and resource sharing within the team and across wider networks to gain access to certain publications and grey literature was essential. Online resources such as the Ross Archive of African Images assisted the process, enabling the team to crosscheck the provenance of certain objects.

After this research, project researcher Imogen Coulson met with Prof. Dr. Barbara Plankensteiner either online or in person to go through the data and decide whether to include certain objects. At this point, additional information may have been needed, or the wider team was asked to help confirm the review.

The combined expertise of the PIs and project team was fundamental to the review process. In particular, Prof. Dr. Barbara Plankensteiner’s knowledge of Benin collections and objects across Europe, the US and Nigeria, as well as Prof. Kokunre Agbontaen-Eghafona and Dr. Felicity Bodenstein’s knowledge of the collections held at the National Museum Lagos and National Museum Benin City. Certain types of objects, such as Ama, Uhunmwu-Elao and Aken’ni Elao, are typical examples of Benin ‘royal court arts’. These objects are the most frequently published and exhibited, and have been the subject of research projects and studies (e.g. Blackmun, 1984on altar tusks; Gunsch, 2018on relief plaques; von Luschan, 1919; Struck, 1923; Fagg, 1963; Dark, 1975; Werner, 1970, and Junge, 2007on commemorative heads). Consequently, the decision-making process regarding these was more straightforward. However, as objects continue to be made today, it is always crucial to look at all the available data about an object to ensure they fall within the project’s parameters. Therefore, even when relatively straightforward, a case-by-case approach was adopted because of the subjective nature of reviewing objects, particularly remotely.

Outside of these ‘typical’ objects, the review process was more complex and revealed some of the many uncertainties and grey areas. Objects which were less well known, researched or published were harder to assess. For example, Aza – iron objects conical in form with a clapper and knife-shaped handle – were not frequently published in recent works on the royal court arts of Benin and not known by the project team. Through discussions with Eiloghosa Obobaifo, who was able to talk with experts in Benin City, it became clear that these objects were used for ritual purposes in Benin, and still are to the present day. Through research I (Imogen Coulson) carried out into published and unpublished literature (e.g. Rosen, 1989, p.44; ‘Nevins, HN’ Wellcome Collection WA/HMM/CM/Col/73), we were able to confirm these objects fell within the project’s parameters and should be included in the catalogue. The combined knowledge of the project team, and in particular collaboration between researchers based in the Hamburg and the Benin City offices, was crucial for these lesser-known objects.

Once the objects were reviewed, the decision was communicated to the relevant institution. If requested, additional explanation was provided, or members of the team met online to answer questions or queries. The decisions were then communicated internally within Digital Benin to the data engineer, Gwenlyn Tiedemann, who started processing the data for further development and research on the platform. Read more about these next steps in the Data Management and Data Acquisition documentation.

Between June and July 2022, a final review of all objects was carried out to ensure that they met the project parameters. This entailed working through the catalogue institution by institution to identify any objects which did not fit within the parameters. In the course of the project, a small number of museums had published provenance reports (e.g. Bedorf, 2021; Hans, Lidchi & Schmidt, 2021; Hicks, 2021) and some museums have also announced returns of objects to Nigeria (e.g., German national museums; Smithsonian Museum of African Art, Washington DC; Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge; Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford; Horniman Museum, London; for an overview, see Atairu, 2021). A comparison between these provenance reports, the announcements of objects to be returned and the datasets also proved to be crucial to check for consistency. Because of ongoing external research along with staff changes during the project, the final review was necessary to ensure a consistent approach.

National Museum Lagos & National Museum Benin City

A separate process was undertaken for the two participating Nigerian institutions, the National Museum, Lagos and National Museum, Benin City. Godfrey Ekhator and Eiloghosa Obobaifo lead the digitisation process in the National Commission for Museum and Monuments (NCMM) in Benin, Owo and Lagos by visiting the institutions multiple times during the project to photograph and record relevant objects and information recorded in catalogue cards, logbooks and inventory books. Prof. Dr. Barbara Plankensteiner also took part in a visit to the NCMM in Lagos to photograph objects, and Prof. Kokunre Agbontaen-Eghafona advised on objects which needed to be included from the National Museums in Lagos and Benin City. More can be read about this process in the digitisation in the Ẹyo Otọ documentation page.

Since the records for objects held in the collections of these two museums were not stored in a digital database, they first needed to be digitised before reviews of the object information could begin. Eiloghosa Obobaifo digitised over two thousand object catalogue cards from the institutions in Nigeria and brought them into a preliminary database that the project team could access internally online. A digital process of reviewing these objects using the digitised records was then undertaken by Godfrey Ekhator-Osasionor, Dr. Felicity Bodenstein and Prof. Dr. Barbara Plankensteiner with assistance from Imogen Coulson. The PIs and project team members recorded whether or not the objects should be included on the platform and added any necessary comments.

Conclusion

Digital Benin acts as a platform to enable and stimulate future research and knowledge production around Benin objects and Edo heritage more broadly, particularly within Nigeria and Benin Kingdom. To create this teamwork was essential: cooperation between the PIs, the project team and our own wider networks was fundamental. Although for each institution the exact process varied depending on the nature of the data provided, the objects and institutional resources, this approach allowed Digital Benin to be as consistent as possible in reviewing object information and digital material that all institutions provided.

By documenting the object research and review process we aim to provide transparency regarding how objects were selected for inclusion on the platform. This review took place only with the data provided, and when possible included PIs’ and team members’ prior knowledge and experience of the institution and objects in question. This in part was due to constraints in time and scope and, to a lesser degree, the coronavirus pandemic, which prevented travel to institutions. The decisions made for this review must therefore be understood as the consequence of the available data. The object data presented on the platform represents the results of research carried out over a period of less than two years; thus, the possibilities for more long-term research are manifold.