Date of document publication: 2022-11-07

Introduction

This proposal investigates the use of derogatory, racist and harmful language within the Digital Benin platform. While the terminologies and terms displayed on the platform are sourced directly from third party sources i.e museum catalogs, it asks what responsibility does Digital Benin have in replicating, showcasing and disseminating this material? In what ways can harm arising from harmful and prejudiced terms be mitigated in light of sensitivities towards source communities? And finally what are some practical steps towards achieving this?

Drawing on existing academic literature and personal experience, it is my hope that this proposal informs decisions that lead to ethical, equitable and transparent readings of artworks and artifacts. This exploration seeks to shed light on the pertinent issues surrounding the replication of harmful colonial language within digital platforms, it is not intended to be a conclusive framework.

An unparalleled forum of knowledge

“As an unparalleled forum of knowledge, Digital Benin will, within the next two years, bring together object data and related documentation material from collections worldwide and provide the long-requested overview of the royal artworks looted in the 19th century” - Digital Benin press release

More than a century since the Benin bronze collection was looted , Digital Benin presents the first opportunity to centralize and view all artifacts through a single platform. This in itself presents a radical departure as the Benin bronze collections have not been viewed in a centralized location since their violent removal. It is uncertain if and when the physical collections will ever be viewed together as currently made possible via the digital platform.

Therefore the significance of this intervention cannot be understated; it offers innumerable opportunities for users to engage and interact with collections, bring in alternative perspectives and shift critical discourse on the representation and documentation of what has now become emblematic of Africa’s thriving pre-colonial civilisations .

As the platform promises to be most beneficial to Nigerian scholars and audiences who have traditionally been disenfranchised from accessing the material, it is important to consider this demographic as a main entry point into the collection. By extension it will also be beneficial to audiences of African descent situated all over the globe. In this regard we ask, What worlds can we construct and reconstruct now that this data is available? What freedoms can be imagined when the limitations of geographies, museums and barriers to access are removed?

Most certainly many communities and descendants in proximity to this history will find Digital Benin to be a great resource. Yet while presenting untold promise, the potential for digital technology to further replicate the violence of the colonial encounter and its far reaching effects still stands. It’s therefore dangerous to make broad assumptions that Digital Benin will benefit everyone equally and that all audiences will respond to the material in the same way.

At the heart of this proposition is the question: How does Digital Benin reconcile its aim to collate material from museums all over the world with the need to center the humanity of the descendants / audiences whose culture is represented on the platform?

It is important to bear in mind that in the absence of physical experience, digital collections will be forced to do the heavy lifting of communicating the history/complexity of the objects while balancing the expectations of those who come to the platform seeking to reconnect with their ancestral pasts. In this regard the impact of language and tone is most central to the user experience. .

Impact of Tone and Language

The suitability of colonial catalogs in adequately representing the ephemeral, spiritual and historical qualities of indigenous material has long been contested in scholarship and practice. An Imperial War Museum study on the impact of language on user interpretation found that language and tone heavily influence audience engagement and understanding (Pringle, 2022). This is also demonstrated by the work of Laura Gibson who in working with Zulu communities to ascribe and describe their collections found that community members depart significantly from existing museum descriptions. (Gibson, 2016)

This in itself becomes not just an issue of language use it is also an issue of knowledge control. In the context of harmful terms it is important to interrogate not just what was said, but how and why it was said. What is the intention of the words? What messages do they convey both about the objects and the people who created them? Whose knowledge is valued and recorded and whose is erased and disdained?

An epistemic framework in which people are only identified by race, ethnic group and in which their rich and complex cultural contexts can only be viewed as lesser, primitive forms lies at the heart of language use within museum collections.

The work of critically reflecting on derogatory terms in museum collections requires the recognition that colonized peoples also have the opportunity to reject these terms and the agency to view and understand themselves beyond the imperial logics forced upon them.

Thus an insistence to preserve these terms / keep using them as is, is not so much about preserving history as it is about preserving power and imperial logic. As argued by several scholars, ways of ordering and structuring knowledge are not set in stone. While museums have traditionally established themselves as authoritative knowledge producers, this knowledge now comes to the fore in an age where we simply cannot look away and claim no part in actively reproducing it.

“Imperialism’s greatest victory was, perhaps, creating an acceptance that we have no option but to depend on such “assertive authority” as embodied in the characters in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness—Kurtz, the white man in the jungle, or Marlow, yet another white man—because the system has “simply eliminated” all alternatives, making them effectively “unthinkable” (Mudimbe)

Harmful language that is presented as immovable and fixed therefore has real consequences beyond digital encounters. The stereotypes and representations it perpetuates, can lead to mental distress, cyberbullying and the continuation of racially targeted violence. While sticking to the proposition that history must remain unchanged and be presented as is, we must also remember that people's lives, livelihoods are affected often with devastating and debilitating consequences largely by stereotypes and language.

Findings / Recommendations

Based on the brief analysis presented above, the following findings / recommendations are made in regard to harmful language use on the Digital Benin platform.

- To continue to display harmful terms would be a continuation of colonial violence that could lead to further digital, mental and physical harm / distress of the communities represented.

As a core priority, Digital Benin should seek to prevent and mitigate any forms of harm that would be directed towards source communities through the widespread accessibility of this material.

As represented earlier, harmful and racilased descriptions have devastating consequences in the digital and real world, while it is impossible to predict how every single user will use this data, the possibility of targeted harm as a result of it, is not inconceivable.

A critical step in the area of decolonial work is an opportunity for digital work to be self-reflective within teams and that this labor is not just done by source communities who are often retraumatised by the material, but by Western scholars and museums as well. Even though the material is sourced from third parties, by not addressing this harm or leaving material as is, the platform may be complicit in furthering colonial and imperial legacies that still impact audiences today.

- User warnings, Anti-racist positions need to be explicit clear and action oriented.

It is important for the platform to establish an explicit and agreed upon ethical / anti-racist / anti-colonial position that is clearly communicated to users upon arrival to the platform. This could be a pop-up message or a message embedded onto a visible part of the platform such as footer, homepage etc.

The erasure of problematic and offensive terms does equate to the removal of problematic context and histories (Pringle, 2022). The effects of the plunder of the Benin kingdom may never be fully understood. The fact that this material is still physically held by Western museums is still a source of discontent for many.

A message such as this could also warn users of the sensitive nature of the material. Providing a layer of interpretation that could increase user confidence and awareness.

Sensitive Content Warning - Sample (To be reviewed and edited)

Digital Benin collates material from museum catalogs all around the world, some of this material is inherently colonial in nature and contains words, terms and phrases that are inaccurate, derogatory and harmful towards African and African diasporic communities. Apart from catalogs, book titles, exhibition titles and museum titles may also contain harmful terms.

We recognise the potential for the material to cause physical and mental distress as well as bring up strong emotions.

We have made efforts to mitigate the harm through the following means: In some cases some words have been redacted and in other cases we have situated alternative words next to problematic ones . However due to the scale of the collections this process is still incomplete.

We would like to state that the material within the catalogs is not representative of Digital Benin’s views. Digital Benin maintains a strong anti-colonial, anti-racist position and affirms its support towards centering the humanity of historically marginalised and disenfranchised communities.

If you encounter material that is distressing and harmful you may write to us at…..

- Opportunity for Digital Benin to shift museum

The unparalleled nature of Digital Benin also presents the opportunity to push museums to be introspective about their own practices. As provenance and collections data becomes more openly accessible, what methodological changes and practice changes can museums make to their internal and externally facing content?

Making changes to cataloging practices has far reaching effects on user interpretation and wider social political attitudes towards history. If carefully constructed, digital catalogs might simultaneously expose and disrupt rigid classification and cataloging systems (Gibson, 2016).While this may not necessarily be the remit of the Digital Benin project, future considerations can develop a guide for museums to interrogate and recatalog Benin bronze collections.

Proposed Actionable steps

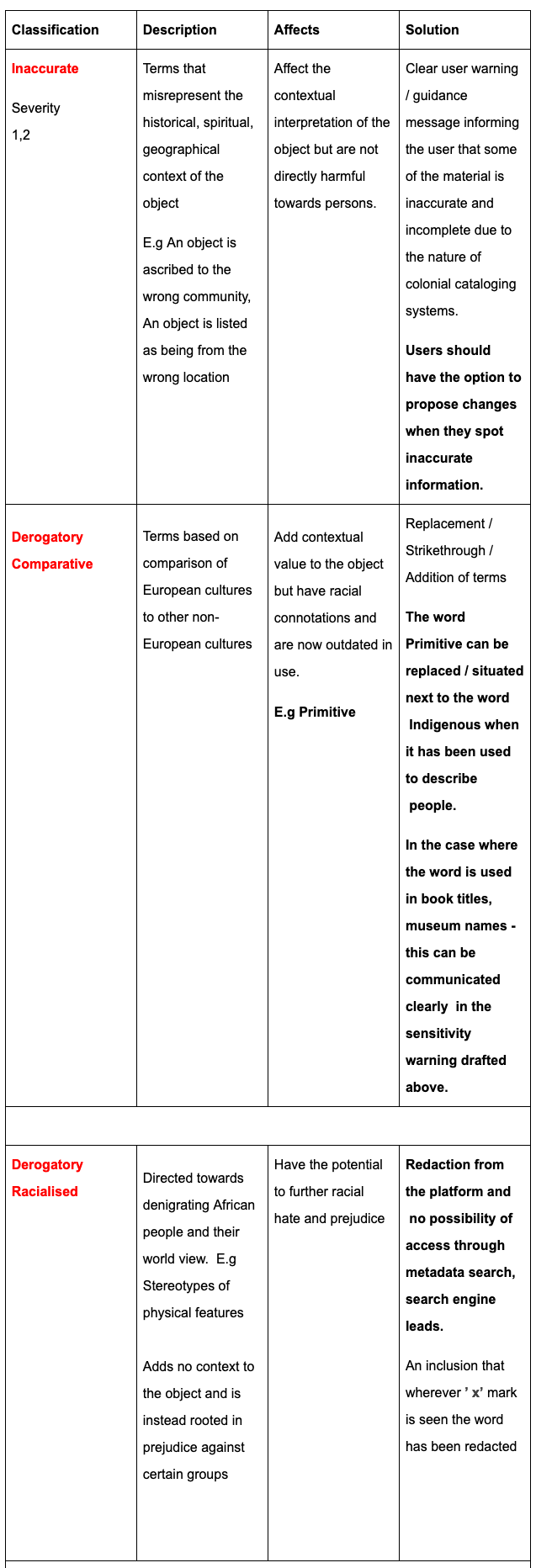

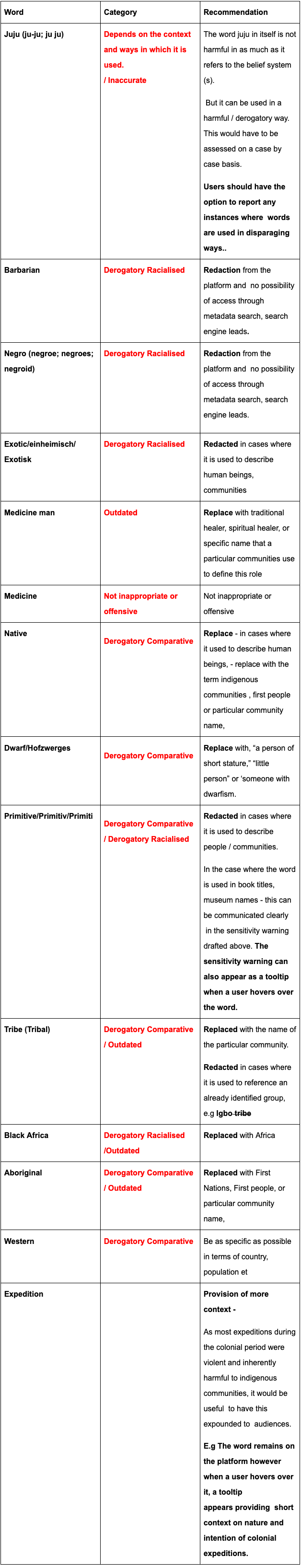

The matrix below proposes some steps to mitigate harm depending on severity of language used.

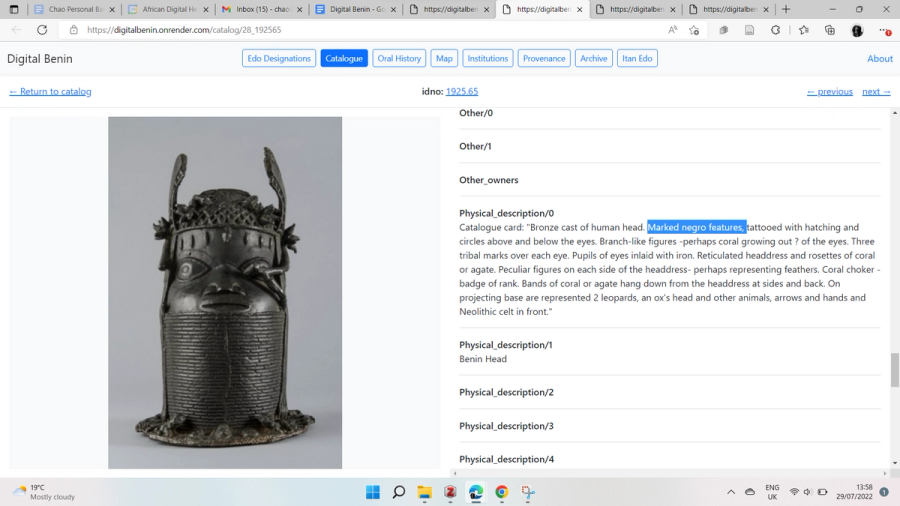

idno: 1925.65

Marked negro features - Here the word Negro is used directly in reference to racial stereotypes and descriptions of persons.

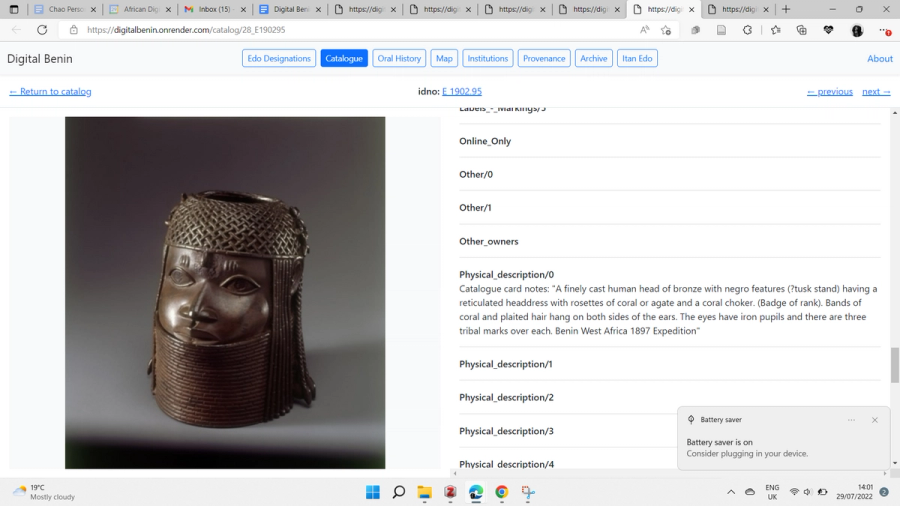

idno: E 1902.95

Head of Bronze with negro features - Here the word is used in direct reference to racial sterotypes

Further Recommendations

Bibliography

- Gibson, Laura. “Decolonising South African Museums in a Digital Age: Re-Imagining the Iziko Museums’ Natal Nguni Catalog and Collection.” : 518.

- Lynch, Bernadette T., and Samuel J.M.M. Alberti. 2010. “Legacies of Prejudice: Racism, Co-Production and Radical Trust in the Museum.” Museum Management and Curatorship 25(1): 13–35.

- Mudimbe, V. Y. 1988. The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge. Bloomington, Ind. ; London: Indiana University Press ; Currey.

- Pringle, Emily. “Provisional Semantics: Addressing the Challenges of Representing Multiple Perspectives within an Evolving Digitized National Collection.” : 48.